Behavioral Economics and Society’s Readiness for Change

Aigul Zabirova,

Chief Research Fellow

at the KazISS under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s 2025 Address sets the direction for reforms and outlines a nationwide path of change. However, the change requires more than programs and numbers, it also depends on people’s readiness. How is society meeting these challenges? And what can Nobel Prize winners teach us in this regard?

The President’s 2025 Address is not just a list of tasks, it is an invitation for society to change alongside the country. His central message is clear: the world is changing at an unprecedented pace, and Kazakhstan must not only adapt to this turbulence but make a decisive leap into the digital era. The President emphasized: “Our younger generation must live in happiness and prosperity. To achieve this, we, as one nation, must work diligently.” The idea is simple yet powerful: no reform will succeed unless people believe in change. The real question is, how ready are we?

What do KazISS Survey reveal?

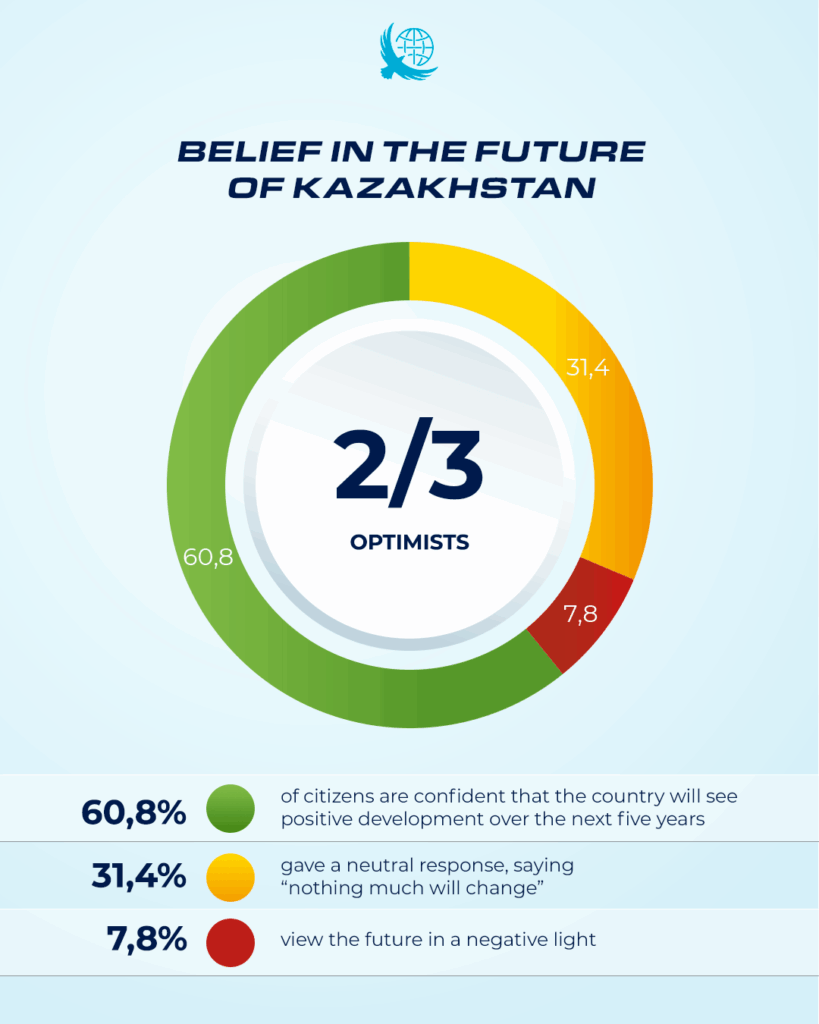

The results of our spring survey are telling:

- 60.8% of citizens are confident that the country will see positive development over the next five years;

- 31.4% gave a neutral response, saying “nothing much will change”;

7.8% view the future in a negative light[i]

Today, Kazakhstan possesses a rare resource of public optimism. Two-thirds of citizens look to the future with hope, meaning that society is not starting from scratch. This very resource becomes the foundation for real action. And here, the ideas of behavioral economics come into play. We turn to the insights of three Nobel laureates who have profoundly influenced modern economics and demonstrated that meaningful change requires not only numbers, but also an understanding of human nature.

1. Richard Thaler’s “Nudge”[ii]: We can improve decision-making without taking away people’s freedom of choice.

In his 2025 annual Address, the President appeals to a new tax mentality and to taxpayers’ honesty, which requires special effort, as it deals with habits, attitudes, and, ultimately, the very culture of behavior. This is precisely what Nobel laureate Richard Thaler, awarded in 2017, wrote about when he introduced the simple yet powerful concept of “nudges.” His idea is that people’s behavior changes not so much through orders and prohibitions, but through the smart design of choices. Thaler demonstrates how behavior can be guided by simple, convenient mechanisms and prompts. In Thaler’s logic, this means the need for online calculators and transparent digital services, where every citizen in Kazakhstan can clearly see how their taxes are returned in the form of schools, hospitals, and roads. When the choice to “pay taxes” becomes understandable, convenient, and even beneficial, people stop looking for ways to bypass the system. Nudges make the right behavior natural and this becomes the step from intention to practice.

2. Daniel Kahneman’s cognitive biases [iii]: We do not think in terms of logic, but rely on quick rules of thumb which often lead to mistakes.

In his annual Address, the President emphasizes the need for society’s readiness for change. Here it is useful to recall the discoveries of Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky, who showed that people do not assess the world rationally, but through cognitive biases. Their famous Prospect Theory demonstrated that losses are felt more acutely than gains. In other words, even if a reform brings long-term benefits, people tend to cling to the familiar because they fear losing what they already have. Kahneman’s “loss aversion” explains why part of society is cautious. People are not opposed to change, they simply want to be assured that they will not lose stability. This makes it crucial to provide guarantees and to explain reforms in clear, simple language: what exactly will change and why. Addressing this psychology, reducing anxiety, and offering transitional mechanisms will reinforce the President’s vision not only of decisive reforms, but of reforms that are psychologically comfortable for society. For example, the introduction of artificial intelligence into the labor market is often met with anxiety: “robots will take all the jobs.” But if people are shown what new professions will emerge, which retraining programs are already available, and how exactly the state will support them, fear can be transformed into readiness. Likewise, if society understands a new tax code only as “we will have to pay more,” people will naturally resist. But if it is explained that taxes guarantee that schools in their neighborhoods will remain open, doctors will receive fair salaries, and roads will be repaired on time, the perception changes. It is no longer about “loss,” but about the fear of losing the well-being that matters to everyone.

3. Robert Shiller’s Narrative Economics[iv]: Financial bubbles are born not on the stock exchange, but in people’s fears, hopes, and stories.

The President’s vision of a Digital Kazakhstan is not merely a technocratic program, it is a story, narrative. A story about a country that can become part of the new world, not fall behind, but break ahead. What matters is how this story is told to the people. Nobel laureate Robert Shiller introduced the concept of narrative economics. The essence of his idea is strikingly simple: economic processes are driven not only by numbers and laws, but also by the stories people believe in. People believe in narratives of growth, decline, and the future.

Shiller also emphasizes that the success of reforms depends largely on citizens’ personal experience. For Kazakhstan, this is especially significant: two-thirds of citizens believe the future will be better. Supporting a narrative means telling stories of success by showing new schools, new jobs, and new digital services. If digitalization is perceived as a guarantee of accessible healthcare, fair taxation, and the protection of children, it will resonate with the public and generate momentum for change. Shiller demonstrates that it is precisely such stories that create what sociologists call the “social glue.” In this sense, the President’s idea of happiness for future generations is itself a narrative that must be repeated and made concrete.

Thus, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s 2025 annual Address unites the nation around a course of change, while the ideas of behavioral economics broaden its meaning, turning society’s hope into concrete action. With reliance on both evidence and human nature, Kazakhstan is poised to step into the new world with confidence, as a country where change becomes a shared effort and a shared story.

[i] The sociological survey was commissioned by KISI and conducted between March 20 and April 20, 2025. The sample size included 8,001 respondents. Participants were citizens aged 18 and older from 17 regions and the three cities of national significance Astana, Almaty, and Shymkent.

[ii] Richard H. Taller. From Cashews to Nudges: The Evolution of behavioral Economics. www.nobelprize.org

[iii] Daniel Kahneman. Maps of bounded rationality. www.nobelprize.org

[iv] Robert Shiller. Speculative asset Prices. www.nobelprize.org