Aigul Zabirova,

Chief Research Fellow, KazISS under the President

of the Republic of Kazakhstan

Everyday life and interpersonal relations increasingly reflect modern ideas, emphasizing opportunities rather than limitations. People no longer see a working mother as harmful to children. They do not automatically allocate jobs to men. They do not see it as a problem when a wife earns more than her husband. And finally, they no longer consider higher education to be more important for boys than for girls. This is not a revolution, but a gradual mature of society, learning to trust its own future.

The idea that higher education is more important for boys than for girls may appear to concern academics and degrees. In reality, it reflects an outdated gender paradigm, in which education is valued less as a pursuit of knowledge and more as a symbol of male responsibility – to study, achieve, and not disappoint. That is why responses to this question reveal not attitudes toward learning, but beliefs about how life should be structured, who is allowed to strive forward, and who is expected to remain modest.

According to a survey conducted for the KazISS[1], the majority of Kazakhstani citizens (71.4%) do not support the idea that higher education is more important for boys than for girls. There are clear reasons for this, which become obvious if we look at how Kazakhstan has changed in recent years. Three major forces have shaped this perspective:

- Governmental Policy,

- international integration

- the country’s socio-economic modernization

Over the years, the state has consistently incorporated the idea of gender equality into its policies and programs. Gender indicators, developed based on the Millennium Development Goals and other international conventions, have gradually been integrated into all of government key strategies. In practice, it is quite straightforward: when every strategy sets goals for equality, and reporting is structured around equality, over time it becomes part of the common language. This, in turn, establishes the standard by which society begins to understand what is considered normal and what is not.

Kazakhstan has actively participated for many years in international initiatives on gender equality, ranging from the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal No. 5 to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. While these commitments may sound formal, in reality they have a straightforward effect. When a country commits to such obligations and participates in global indices, such as those of the World Economic Forum, it establishes an external framework that it cannot easily ignore. Consequently, the notion that ‘higher education is more important for boys’ eventually ceases to function merely as an outdated social norm and comes to be understood as a practice inconsistent with international standards.

Ultimately, societal developments prompt a reconsideration of perspective. As the economy grows increasingly complex and educational opportunities expand, women’s participation transcends ideological discourse to become a practical necessity. Kazakhstani women are entering the workforce, pursuing careers, and engaging actively in public life—developments that are now broadly accepted.

Gender equality advances, and as a country becomes more urbanized, mobile, and educated, this progress occurs almost automatically. Against this backdrop, the belief that education is more important for boys appears as a vestige of a bygone era.

This combination of three key forces is shaping a society in which the idea that “education is more important for boys” has become morally outdated for the majority, while it is still upheld by groups embedded in more traditional economic and cultural contexts.

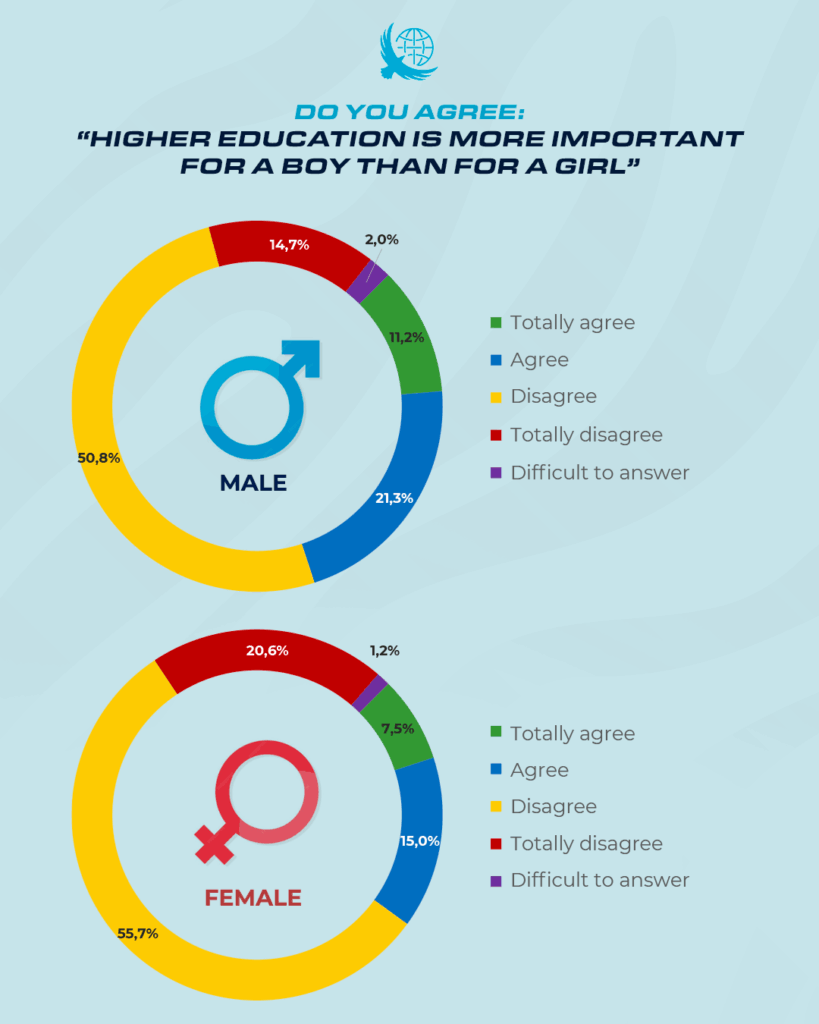

Thus, as we can see, most Kazakhstani citizens no longer adhere to the old gender order, yet its core (27%) remains persistent, particularly among men, rural residents, individuals with lower socioeconomic status, and religiously observant individuals. Men are more likely to support the idea of prioritizing education for boys (32.5% versus 22.5% among women). This is not about personal interest; rather, it reflects a justification of traditional responsibilities—if a man is expected to provide for the family, education as a tool for social mobility is perceived as being primarily his domain. Women, by contrast, are more likely to disagree, which is understandable, as the educational mobility of Kazakhstani women has long exceeded the confines of traditional roles (Table 1).

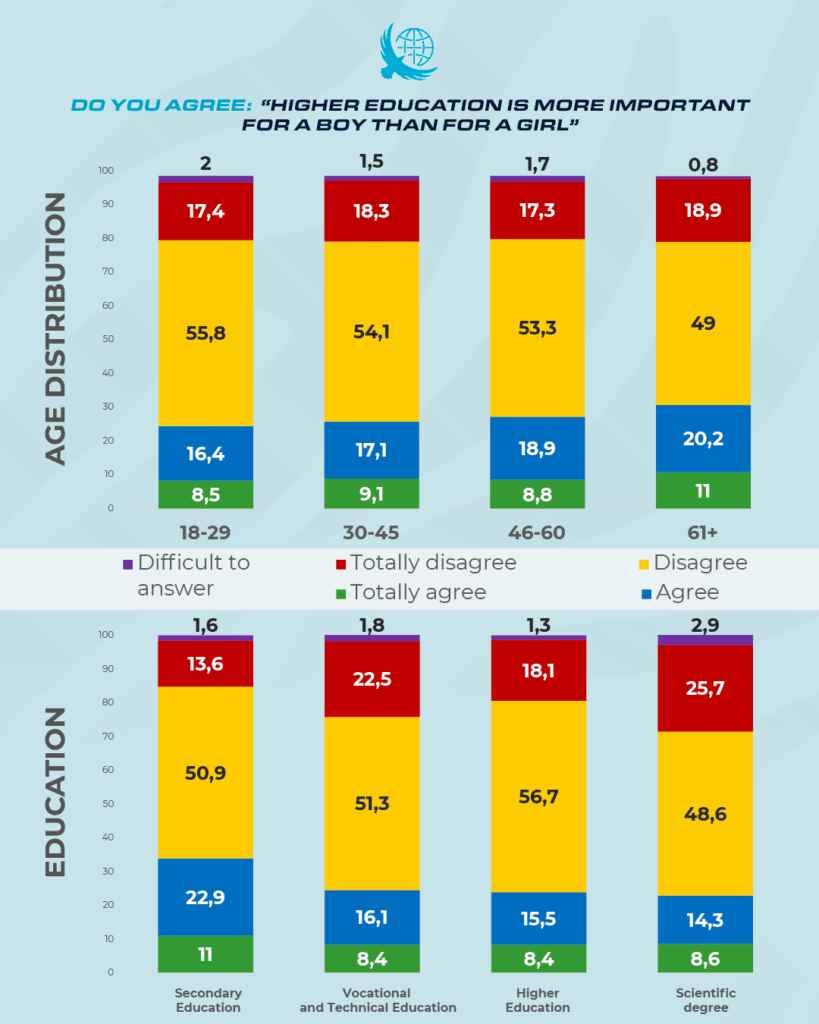

The older the age group, the greater the agreement with the idea that higher education should be prioritized for boys. Younger respondents are less supportive of this notion, but as observed, the differences are relatively minor. There is no generational conflict; rather, this reflects a gradual weakening of traditionalist attitudes across all age groups (Table 2).

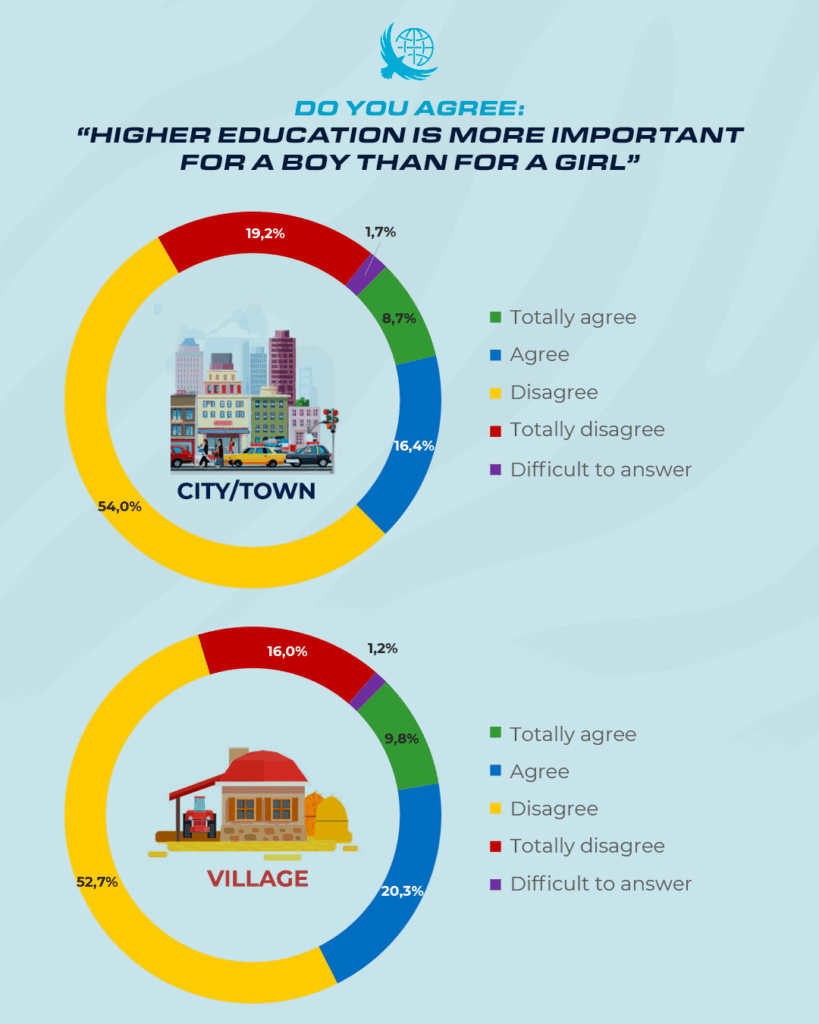

Support for prioritizing boys’ education is higher in rural areas, reflecting a classic pattern in which distinctions between male and female labor remain significant in agriculture. The traditional role of ‘man as provider’ endures longer in these contexts. In urban areas, however, competence rather than gender determines outcomes, which helps explain why fewer people believe that education should be allocated according to sex (Table 3).

The highest proportion of respondents who believe that ‘higher education is more important for boys’ are those with a secondary education (33.9%). The higher the respondent’s level of education, the less prevalent this belief, which is logical: the more engaged an individual is in the modern economy, the less likely they are to adhere to traditional gender roles.

Religiosity stands out as the strongest factor: among observant believers, 44% support the belief that ‘higher education is more important for boys,’ nearly twice the average. Clearly, from a religious perspective, the gender order operates as a moral framework, where men are expected to take responsibility and lead, while women are assigned the role of family caretakers.

Among lower-income groups, the share of those who believe that “higher education is more important for boys” is also higher, reaching up to 34%. This is understandable: when resources are limited, society seeks to optimize opportunities, since education remains an expensive resource. In other words, both cultural and material mechanisms contribute to the reproduction of inequality.

Even with this traditional core still present, the overall picture looks different. If we take a broader view not just one question, but all four in the series on gender covering working mothers, male dominance in the labor market, family income, and education for boys and girls, a clear trend emerges. While traces of the old gender order still persist, everyday life and interpersonal relations increasingly reflect modern ideas, emphasizing opportunities rather than limitation.

People no longer see a working mother as harmful to children. They do not automatically allocate jobs to men. They do not see it as a problem when a wife earns more than her husband. And finally, they no longer consider education to be more important for boys than for girls. This is not a revolution, but a gradual maturation of society, learning to trust its own future. The future is becoming increasingly open and equitable for both boys and girls.

[1] The survey was conducted from May 11 to June 22, 2024, commissioned by the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies, with 8,101 respondents. Participants were over 18 years old and came from 17 regions of the country as well as the cities of national significance: Astana, Almaty, and Shymkent.