On the Gender Compromise of Kazakhstani Women

Aigul Zabirova,

Chief Research Fellow,

KazISS under the President of the RK

Since the Soviet era, women in Kazakhstan have been engaged in paid work while simultaneously doing housework. This has resulted in a “double role” that has become the norm, though it brings little relief.

Women have long been the backbone of family budgets in Kazakhstan, yet the question of whether maternal employment harms children continue to divide generations. In this sense, Kazakhstan represents a unique case where women’s participation in the labor force coexists with deeply rooted patriarchal values.

Sociologists refer to this situation as the “double shift”[i]: the combination of women’s paid employment and a heavy domestic workload. The causes are clear: financial pressures, limited state support, and a cultural expectation that a “good mother” should devote herself entirely to her children. As a working mother, I would note that this ideal is unattainable. Women are caught between two opposing forces: the economy demands their labor, while the family demands complete dedication at home, in the form of unpaid work. Kazakhstan is not an exception here; the double-shift pattern is characteristic of many post-socialist societies where women participate in the workforce on par with men yet still carry the primary responsibility for the household[ii].

The double shift manifests not only in lived experience but also in social perceptions of women’s roles. Survey data from the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies (KazISS) reveal[iii] that part of society continues to hold patriarchal views, while another part leans toward more modern perspectives. In particular, respondents were asked to evaluate the statement: “When a woman works, it negatively affects her children”on a scale ranging from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree.” Agreement indicated a more patriarchal stance, while disagreement reflected a more modern outlook. Patriarchy in family and gender relations implies male dominance and a restricted role for women. In Kazakhstan, patriarchy takes different forms. Among Kazakhs, strong traditions of kinship and seniority persist; among Uzbeks, patriarchy is expressed through early marriages and rigid household roles; among older generations of Russians, it echoes the Soviet-era norm of “the man as breadwinner and the woman as homemaker.” By contrast, modern attitudes imply equal opportunities and flexible roles: men and women are partners, their achievements in work and education are valued equally, and domestic responsibilities are shared.

Overall, 37.9% of respondents believe that maternal employment negatively affects children, while the majority (59.4%) disagree. We live in a dual reality: women’s employment has become a social norm, yet the expectation that mothers bear the entire burden of family life remains strong.

Who, then, stands behind these figures? Which social groups are more inclined toward patriarchal views, and which adopt a modern stance?

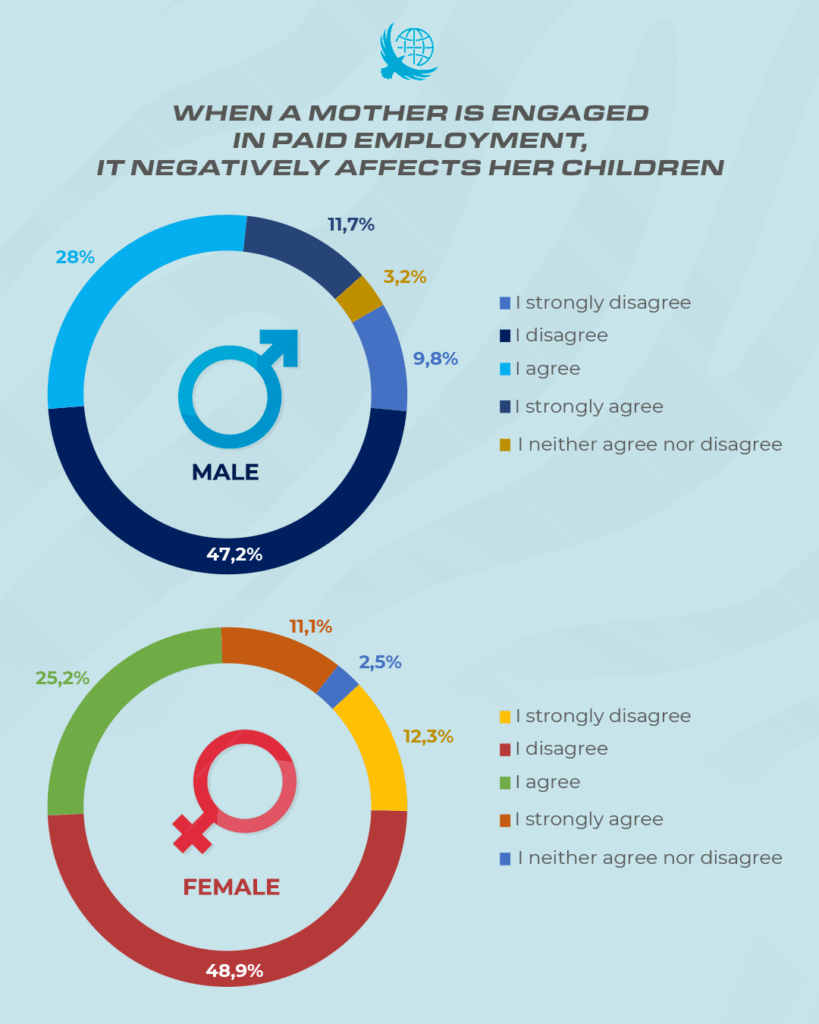

- The gender gap exists but is not dramatic. As shown in Chart 1, men and women’s assessments are nearly identical, though differences remain: correlation analysis indicates a weak but statistically significant negative relationship (Spearman’s rho = -0.049), suggesting that men are slightly more inclined to agree with this stereotype.

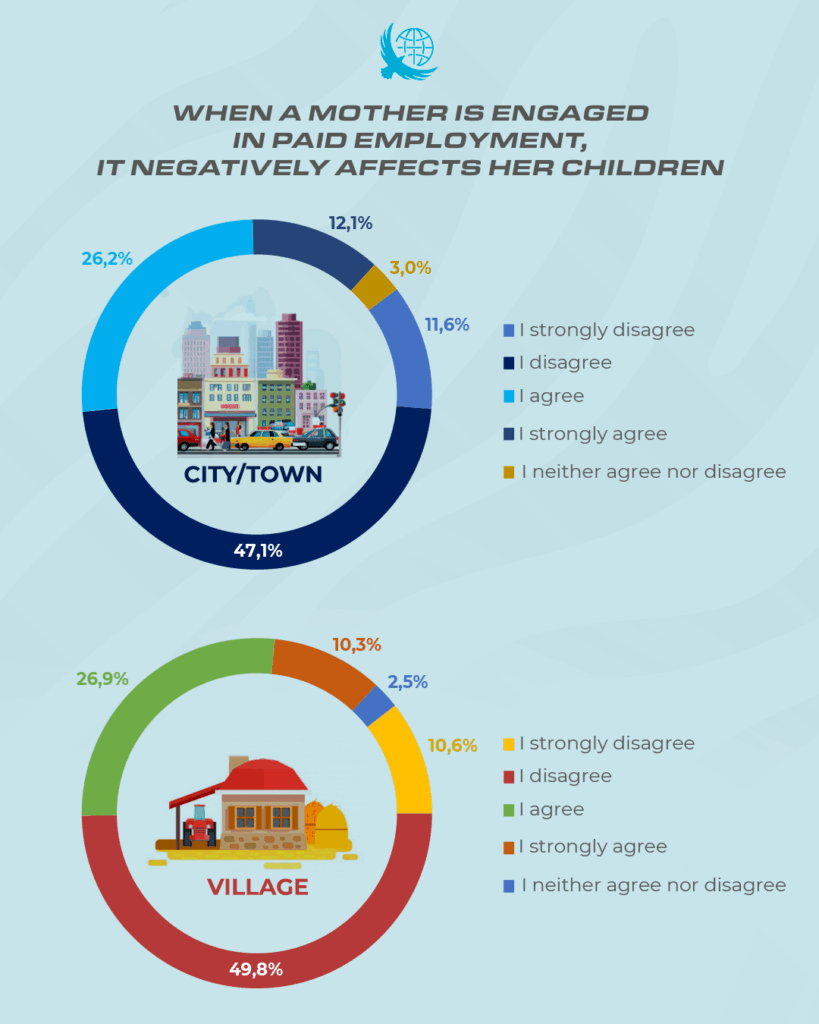

- Urban–rural differences are minimal. In cities, 38.3% of respondents agree with the statement, compared to 37.2% in rural areas (Chart 2). In other words, type of settlement does not divide society into two distinct camps, attitudes toward women’s roles are largely similar.

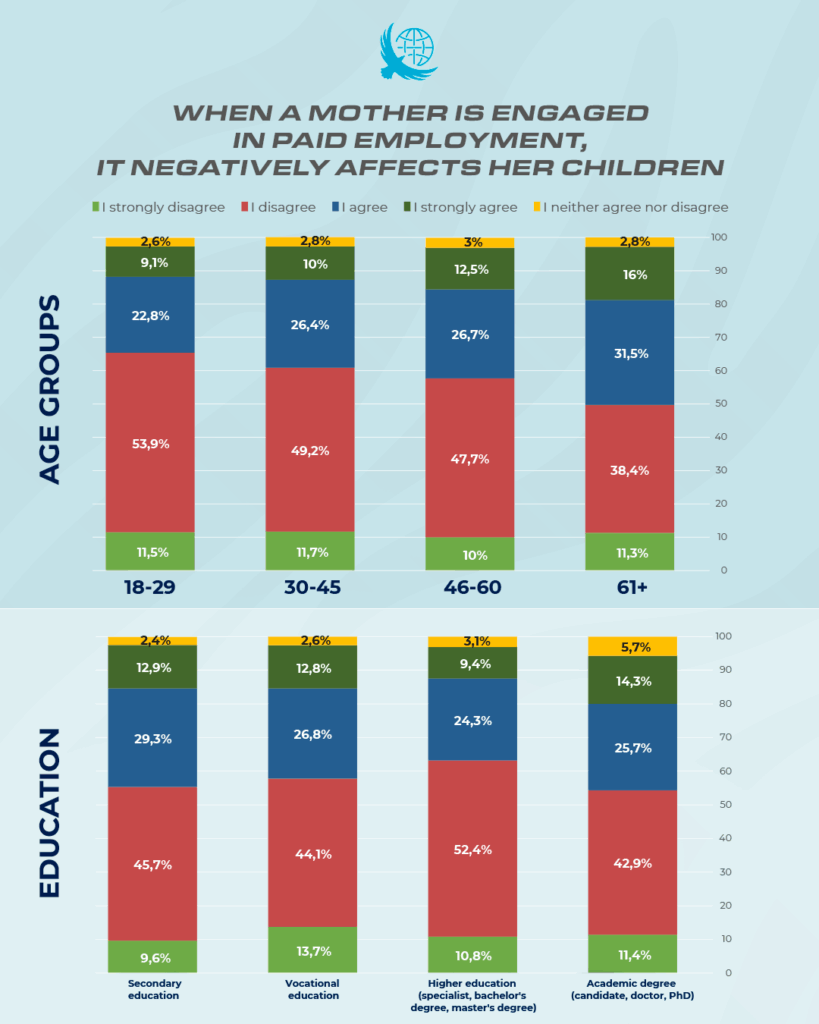

- The higher the level of education, the less agreement with the stereotype. The relationship with education level is not entirely clear-cut. Those with secondary or vocational education are the most traditional, with 42.2% in agreement (Chart 3). Among respondents with higher education, only 33.7% agree. While the correlation is weak, it is statistically significant (Spearman’s rho = -0.057).

- Age emerges as the strongest factor. Attitudes differ most sharply across generations. Among 18–29-year-olds, about one-third (32%) agree that maternal employment harms children, compared with nearly half (47.5%) of older respondents. The correlation is positive and significant (Spearman’s rho = 0.088). Younger generations already perceive the working mother as the norm, while older generations continue to cling to traditional ideals of motherhood.

Logistic regression analysis confirms these findings: age and education are the strongest predictors of patriarchal versus modern attitudes toward working mothers, while gender and place of residence play relatively minor roles.

International sociological research consistently shows that maternal employment does not harm children. What matters most is the support. If the state and society aim to reduce women’s double burden, several steps are crucial: expanding access to childcare facilities, after-school programs, and affordable care services; developing flexible employment arrangements that allow parents to balance work and family; and redefining the role of fathers. An engaged father is not merely a helper to the mother but a foundation for a stronger family and broader opportunities for the child. Finally, the media and education systems play a vital role in reshaping perceptions, demonstrating that a working mother is not a threat to children but a resource for the entire family. Ultimately, when labor and caregiving become shared responsibilities, the double shift ceases to be an unrelenting burden and transforms into genuine partnership.

[i] Hochshild, Arlie Russel, and Anne Mashung. The second shift: working parents and the revolution at home. Penguin, 2012

[ii] Kazakhstan stands as a hybrid case: a society marked by its post-socialist heritage, evolving market dynamics, and entrenched patriarchal traditions.

[iii] Between May 11 and June 22, 2024, a survey commissioned by KazISS was carried out with 8,101 respondents. The sample comprised individuals aged 18 and over from 17 regions of Kazakhstan and the cities of republican significance: Astana, Almaty, and Shymkent.