Why television retains trust despite the rise of social networks and online media

Aigul Zabirova,

Chief Research Fellow

at the KazISS under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan

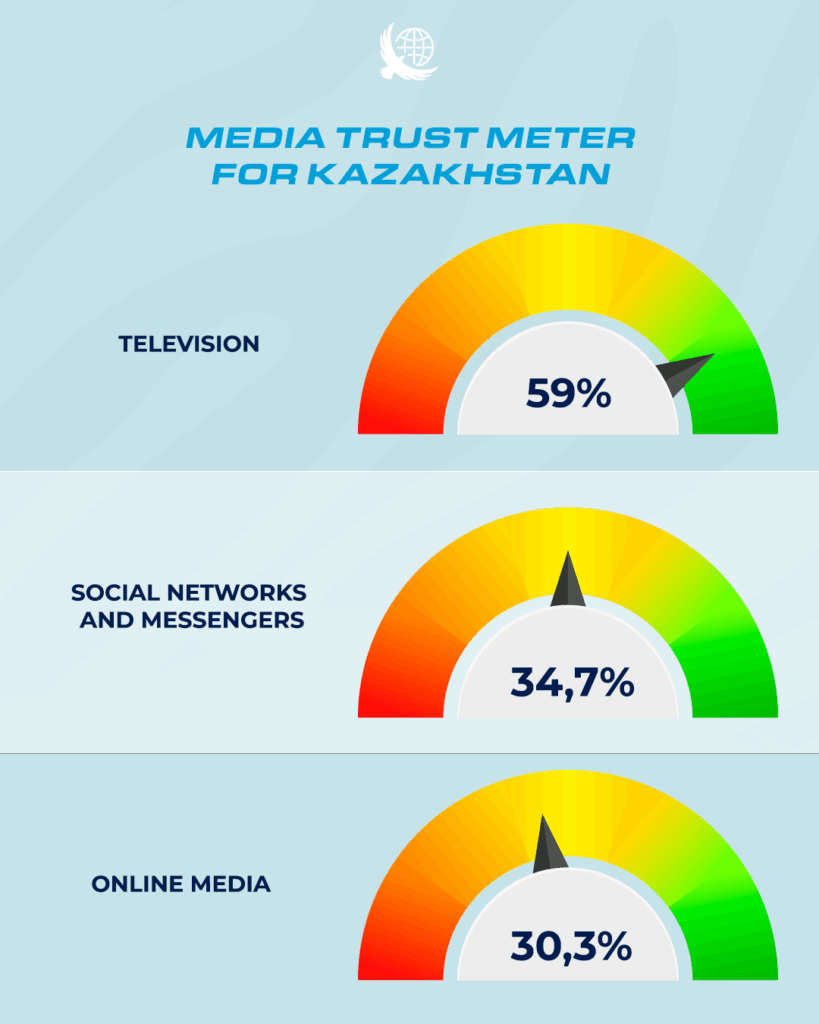

Kazakhstan is developing a hybrid media environment where television continues to hold the lead in terms of public trust, despite increasing competition from social networks and online media. According to KazISS data, 59% of Kazakhstanis trust television, while social networks and messengers receive 34.7%, and online media 30.3%. This dynamic shows that television remains the main channel of trust, but its position is no longer unconditional. In the new information hierarchy, TV channels must defend their status under growing pressure from digital platforms and online communities.

Television as the leader of trust

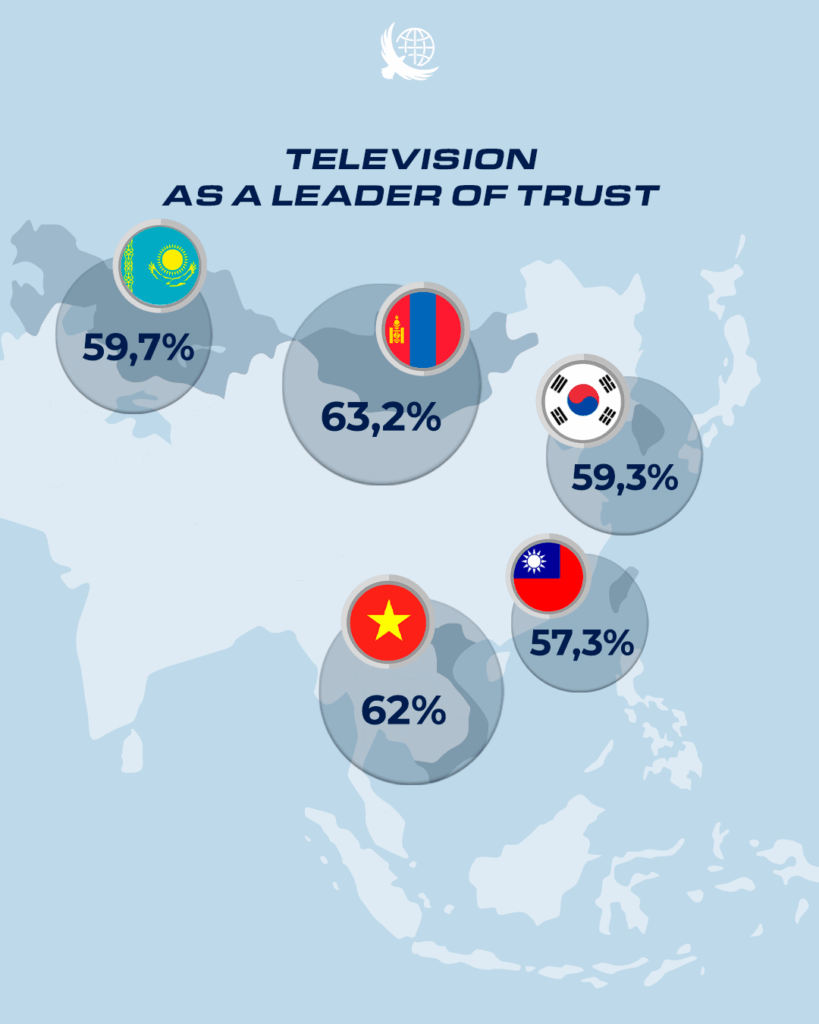

Today, Kazakhstan’s media environment is shaping into a hybrid model: television channels, digital media, and rapidly growing social networks with messengers. At the top of this hierarchy remains television. According to KazISS’s spring survey, 59.7% of Kazakhstanis trust television[i].

When it comes to trust in television in Kazakhstan, the figure of 59.7% may seem high compared to the discussions about the “death of television.” Looking beyond the country to its neighbours in the region, the picture surprisingly repeats itself. According to the Asian Barometer, in Mongolia[ii] 63.2% of the population trusts television, in Vietnam 62.0%[iii], in South Korea 59.3%[iv], and in Taiwan[v] 57.3%. The spread between the maximum and minimum is 5.9 percentage points (63.2–57.3). It shows that all five countries fall within a corridor of moderately high trust in television.

This comparison demonstrates how television maintains a stable level of trust not only in Kazakhstan but across the Asian region. The similarity of trust levels in different countries suggests that this is not about random fluctuations, but deeper foundations.

Two lenses of trust

Why does the screen continue to hold attention? The answer lies in two different dimensions: institutional and cultural.

Institutional lens. Froman institutional perspective, television is an official and stable institution. In Kazakhstan, the country’s largest channels (“First Channel Eurasia,” “Qazaqstan,” “Khabar,” Channel 31, “KTK”) are integrated into the state infrastructure and therefore have unique access to official information. Regular news broadcasts, recognizable news presenters create a sense of reliability. Unlike social networks and messengers, where information often remains unverified, television is perceived as the “proven word”[vi]. Scheduled newscasts, standardized delivery, and familiar news presenters reinforce the parameters of credibility[vii].

Cultural lens. Trust in television is also formed through habits and values. How does it work? Through socialization, values are “absorbed” via the dominant channel (in this case, TV) and then projected onto the evaluation of institutions[viii]. Several generations of Kazakhstanis were socialized through television, and this habit has become part of the collective experience. Moreover, for older age groups, where media literacy is lower, TV remains clearer and more reliable than a news feed on a phone. Therefore, in Kazakhstan, television functions not merely as a device, but a part of everyday life, a symbol of family cohesion and social order.

Hybrid media environment and emerging players

However, in a hybrid media environment, television can no longer remain the only source of trust. 34.7% of Kazakhstanis trust social networks and messengers, which have become a “new space of trust” for personal contacts and online communities. Social networks attract users with their speed and interactivity. Meanwhile, 30.3% of respondents trust online media, which are perceived as fast and modern, though not always as recognized. In turn, the algorithms of digital platforms create a sense of personal closeness and belonging to one’s circle. All this means that television’s leadership must increasingly be defended rather than taken for granted.

In this competition, the essence of the hybrid model reveals itself. Namely, the combination of television’s institutional stability and cultural memory with the dynamism of digital platforms. The key question in this clash is whether television can not only hold its position but also find new ways of engaging with society in a world where trust has become highly contested.

[i] The sociological survey was commissioned by KazISS and conducted from March 20 to April 20, 2025. The sample size was 8001 respondents. Participants included respondents over the age of 18 from 17 regions and 3 cities of national significance – Astana, Almaty, and Shymkent.

[ii] https://www.asianbarometer.org/datar?page=d10 SPSS file for Mongolia dated 23.12.2024.

[iii] https://www.asianbarometer.org/datar?page=d10 SPSS file on Vietnam dated 17.01.2025.

[iv] https://www.asianbarometer.org/datar?page=d10 SPSS file for South Korea on 20.12.2024.

[v] https://www.asianbarometer.org/datar?page=d10 SPSS file for Taiwan dated 02.04.2024.

[vi] Hovland, C.I., Janis, I.L., Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Study of Opinion Change, Yale University, 1953; Mishler, W. & Rose R. What are the origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in post – Communist societies, Comparative Political Studies, vol.34, no.1, pp.30-62, 2001.

[vii] Gaziano, C., & McGrath, K. Measuring the Concept of Credibility, Journalism &Mass Communication Quarterly, vol63, pp.451-462, 1986.

[viii] Müller, J. Mechanisms of Trust: News Media in Democratic and Authoritarian Regimes. Verlag, 250pp.2013; Lee, T. Why they don’t trust the media. American Behavioral Scientist, vol.54, no.1, pp.8-21, 2010.